by Beverly Rosenbaum

Have you ever heard of “DoubleClick?” If not, then finding “cookies” from them on your computer would probably surprise you.

Look and see for yourself. You can search your PC for the file called “cookies.txt” or folder called “cookies” (that’s “MagicCookie” if you use a Mac). Open the file with a text editor and take a look at the contents. If you’ve been doing any browsing at all, you’ll find a cookie in there from someone called “doubleclick.net”.

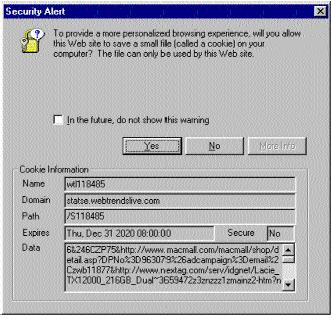

If you’re convinced that you never went to a site called “DoubleClick,” how did they give you a cookie? After all, the idea of the cookie (according to the original specs published by Netscape) is to make a more efficient connection between the server that delivers the cookie and the client machine that receives it. This variant is what’s known as a third-party cookie.

Now

if you connect to the Internet and browse www.doubleclick.net,

you can see their site list of participants (www.doubleclick.com

/us/advertisers/media/brand/site-list.asp) and read all about their data

collection to deliver targeted marketing based on our cookies and our profiles.

What is really happening is that subscribers to the DoubleClick service are

putting a third-party cookie request on their home page for the DoubleClick

cookie. [Every step of the way you’ll collect cookies from them, at least until

you can make your way to the new page they’ve recently added that now provides

you an “Opt-Out” option (www.doubleclick.com/us/corporate/privacy/).]

Now

if you connect to the Internet and browse www.doubleclick.net,

you can see their site list of participants (www.doubleclick.com

/us/advertisers/media/brand/site-list.asp) and read all about their data

collection to deliver targeted marketing based on our cookies and our profiles.

What is really happening is that subscribers to the DoubleClick service are

putting a third-party cookie request on their home page for the DoubleClick

cookie. [Every step of the way you’ll collect cookies from them, at least until

you can make your way to the new page they’ve recently added that now provides

you an “Opt-Out” option (www.doubleclick.com/us/corporate/privacy/).]

So when you hit one of these sites, it requests the cookie from your computer to see who you are, and gets any other information that happens to be in your cookie file. It then sends a request to “DoubleClick” with your ID, requesting all available marketing information about you. Then you’re supposed to receive specially targeted marketing banners from the site. In other words, if you and I log on to the same site at the exact same time, based on our cookie information I might see ads for printers, while you would see ads for cameras. If you log in to a “DoubleClick” enabled site, and it sends a request for your “DoubleClick” cookie, and you don’t have one, then each and every one of those sites will hand you a “DoubleClick” cookie. Pretty sneaky way to roll in the cookie dough, don’t you think?

DoubleClick is the Web’s largest ad company, sponsoring PlazaDirect.com (formerly NetDeals.com), which invites you to sign up for various sweepstakes or catalogs and other “special offers.” That’s how they get you to willingly give them personal information, such as your name, mailing address, and email address.

Fortunately, several privacy organizations have taken up the cause to protect us, because the main concern is that all this could be done without anyone’s knowledge. Even though the use of this information is harmless in itself as long as you know the limitations of these networks, many people still feel that gathering information in this way is invasive to their privacy. Everyone agrees that one of the main issues is awareness.

To

add more information to their collected profiles of individual behavior, DoubleClick

completed a merger in November 1999 with Abacus Direct, a giant in offline marketing

information. Then things got worse; DoubleClick had to personally identify all

the information they previously collected in order to merge it with the data

in the hands of Abacus Direct. By February 2000, the Electronic Privacy Information

Center in Washington, D.C. (www.epic.org)

filed a complaint against them alleging “unfair and deceptive” business practices,

because DoubleClick had deceived consumers by claiming in multiple earlier privacy

policies that the information collected would remain anonymous.

To

add more information to their collected profiles of individual behavior, DoubleClick

completed a merger in November 1999 with Abacus Direct, a giant in offline marketing

information. Then things got worse; DoubleClick had to personally identify all

the information they previously collected in order to merge it with the data

in the hands of Abacus Direct. By February 2000, the Electronic Privacy Information

Center in Washington, D.C. (www.epic.org)

filed a complaint against them alleging “unfair and deceptive” business practices,

because DoubleClick had deceived consumers by claiming in multiple earlier privacy

policies that the information collected would remain anonymous.

Another independent non-profit privacy initiative is TRUSTe (www.truste.org), dedicated to building users’ trust and confidence on the Internet through the use of their oversight seal, awarded to web sites that adhere to established privacy principles and agree to comply with an oversight and consumer resolution process.

In four years DoubleClick served ads and tracked users on more than 11,000 web sites, collecting 100 million profiles of Internet users. Industry analysts estimated that 45.8% of Internet users in the United States visited web sites in the DoubleClick advertising network in a single month. And while a New York court recently announced a proposed settlement in the EPIC litigation, it’s not a total victory for consumers. The settlement would affect all Internet users who “had DoubleClick cookies placed upon their computers or browsers between Jan 1, 1996 and March 28, 2002.” The agreement will, among other things, require future DoubleClick cookies to expire within 5 years. (That’s two years after the typical user has changed computers!) The company will also be required to ensure the protection and routine purging of data collected online. The DoubleClick Opt-Out option was added after the complaint was filed, and the company has also posted a TRUSTe-approved privacy policy. DoubleClick has now become a member of the Network Advertising Initiative (www.network advertising.org/), and are audited for compliance with NAI principles by PricewaterhouseCoopers.

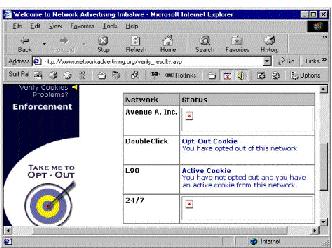

Selecting their offer to let you “opt out” actually provides a persistent “blank” cookie containing the string “id=OPT_OUT,” preventing them from assigning any future cookies or uniquely associating any information with your browser. This way, you can opt-out of the ad-serving cookies without erasing or altering other cookies associated with your browser. Note that if you erase or otherwise alter your browser’s cookie file after opting out (including upgrading certain browsers) you may need to perform this process again. You can opt out of four different ad networks (Avenue A, DoubleClick, L90, and 24/7) at one site through NAI (www.networkadvertising.org/), but that doesn’t cover all the cookies you may find in your cookie jar.

The setting in Netscape or Internet Explorer to accept, reject, or be prompted about cookies is pretty much an all-or-nothing choice versus constantly being asked if you want a cookie (what a polite approach). And don’t forget the related annoyance, pop-up ads. Getting rid of them would require disabling Javascript in your browser, and since many java applets, links and games on web sites run from pop-ups, doing this across the board would not have the best results. So it seems to me that we still need to take the matter of controlling cookies, banner ads and pop-ups into our own hands with customized programs.

I’ve investigated the available freeware and shareware programs to do just that, and I found 61 different programs that work with varying degrees of success. A number of them used an HTTP proxy to accomplish the task, and that can make them difficult to configure if you are using a firewall or already have other applications that require proxy servers. If you get a conflict, your web access can be cut off entirely. Many of the others were much easier to use, and after a great deal of trial and error, I found several that did an adequate job. In the process, however, I discovered that I was being handed cookies with expiration dates ranging from 10 to 27 years from now, and that I got anywhere from 7 to 14 cookies on a single web page, sometimes more. At one time privacy advocates counted 93 cookies from a single site at www.planetrx.com, but most of them have now been removed.

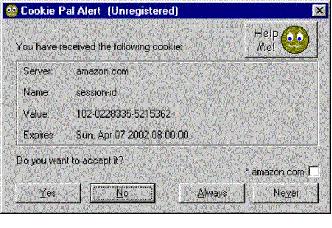

I

tested Cookie Pal, Jar, Smasher, Crusher, Cruncher, Cleaner, and Eater specializing

in just cookie removal, and many more. I finally got comfortable with a combination

of Burnt Cookies (www.andersson-design.com/bcookies/),

which has a $5 registration; Cookie Jar (www.jasons-toolbox.com/cookiejar.asp),

free for personal use; and Cookie Pal (www.kburra.com),

30-day shareware with a $13 registration. I liked Surf Pal from www.panicware.com/

to control both pop-ups and cookies. Panicware’s new update of SurfPal is coming

soon, but in the meantime, you can download the free version or 30-day trial

of their PopupStopper.

I

tested Cookie Pal, Jar, Smasher, Crusher, Cruncher, Cleaner, and Eater specializing

in just cookie removal, and many more. I finally got comfortable with a combination

of Burnt Cookies (www.andersson-design.com/bcookies/),

which has a $5 registration; Cookie Jar (www.jasons-toolbox.com/cookiejar.asp),

free for personal use; and Cookie Pal (www.kburra.com),

30-day shareware with a $13 registration. I liked Surf Pal from www.panicware.com/

to control both pop-ups and cookies. Panicware’s new update of SurfPal is coming

soon, but in the meantime, you can download the free version or 30-day trial

of their PopupStopper.

I also tried the free version of Anonymizer (www.anonymizer.com/) to filter banner ads and scramble my web page requests with a simple plugin to Internet Explorer. It works by rewriting the web pages you view on their protected servers, and I was prevented from reaching www.microsoft.com at all! It noticeably delayed the loading of each page and drove me so crazy with popup windows to upgrade their product to the full version ($49.96 /year) that I couldn’t wait to uninstall it. They even tried to give me a cookie that expired in 2037!

The Privacy Foundation’s free Bugnosis (www.bugnosis.org/) really opened my eyes to the number of third party cookies hidden on various web pages, and I’ve uncovered a great deal more to tell you than I ever expected. Come back next month for more details about controlling popup windows and web bugs you can’t even see. In addition, I’ll tell you about how the same bits of code are now being delivered to you through e-mail in enhanced messages that share the look and feel of Web pages. Since e-mail marketing is not subject to the same policies that have been developed to protect consumer privacy on the Web, we may indeed have a new battle on our hands.

Beverly Rosenbaum, a HAL-PC member, is a 1999 and 2000 Houston Press Club “Excellence in Journalism” award winner. She can be reached at brosen@hal-pc.org.

E-mail me at webmaster@hal-pc.org with any comments you have and tell me what you want to see here.

Back to the Magazine Home Page

Last modified: 2002:05:12